Between nostalgia and future-thinking

Lugemisaeg 8 minFollow-up of the XI Urban and Landscape Days “Socialist and Post-Socialist Urbanisation: Architecture, Land Use and Property Rights” in Tallinn, May 8-11.

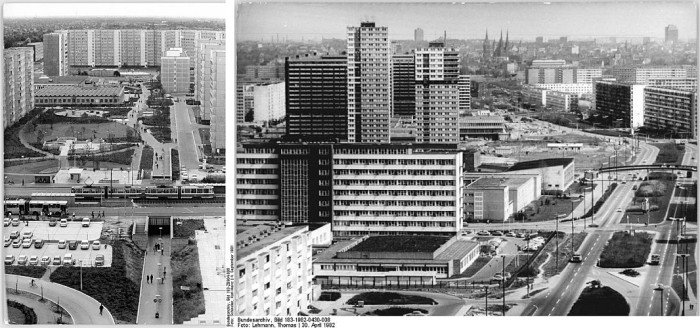

Post-socialism is a complex term which continues to be problematic in many ways, especially within that same “post-socialist” context where it has until recently been treated with certain distance. A change in this discourse in urban studies in Estonia has only happened in last few years – starting from the Venice Biennale in 2012 that asked “How long is the life of a building?” and the Tallinn Architecture Biennale in 2013 “Recycling Socialism”” that focused on reintegrating post-socialist heritage. The topic seems to suddenly, however, be on the forefront of discussions – key terms of urban studies such as landscape, planning and urbanisation have all acquired almost obligatory prefix “post-socialist”. Thus, when we talk about Eastern Europe, some sort of distinctness from the West but also a common ground with the rest of the former Soviet countries seems to be found in ideas of “post-socialist landscape”, “post-socialist urbanisation” and “post-socialist planning”. The annual Estonian Urban and Landscape Days (ULD) addressed the topic under the headline “Socialist and post-socialist urbanisation: architecture, land and property rights”. The ambition was to initiate a fresh investigation in which architecture, land and property rights are looked at in their mutual relationships, since many see the need for putting the term “post-socialism” into context. It seems that some distance was needed in order to start approaching topics that are common in post-socialist urban development. Few months after the event we have an opportunity to reflect on how post-socialism in urban studies and architecture is perceived and presented.

ULD started 11 years ago and it is a great arena to showcase the potential of urban studies in Estonia as well as the capabilities of students for whom organising the event is part of their urban studies course. The four-day conference that brought together speakers from Japan to the US (next to researchers from many European countries) was diverse in content as well as activities. The presentations were accompanied by a poster session, a display of student work analysing Baltic Railway Sation Market as a post-socialist space and excursions organised by Linnalabor that dealt with topics such as restitution (“Urban landscape of restitution”) and housing estates (“The Väike-Õismäe housing estate”). The Estonian Academy of Arts Faculty of Architecture collaborated with the Estonian Urbanists’ Review “U” to publish a special issue. The conference’s focus on architecture, land use and property rights was emphasised by three well curated key note speeches: Stefan Rettich (“Farewell from welfare”), Anne Haila (“The value of land as fiction”), Lukasz Stanek (“Postmodernism is almost all right. From Poland to the Middle East and back”).

Daring critical analysis

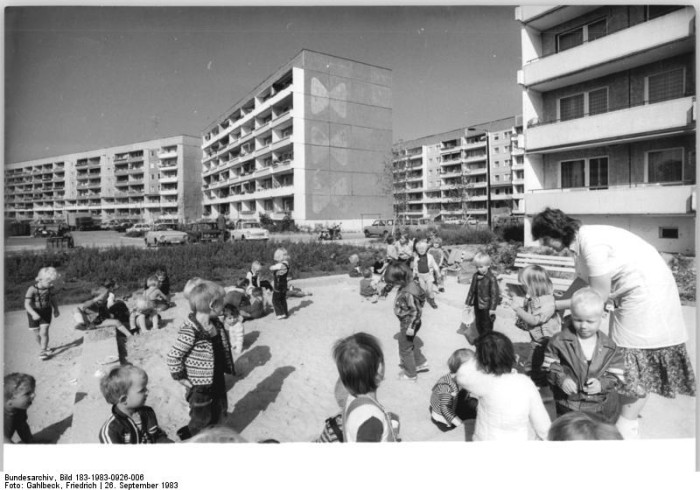

The conference left several major ideas in the air and broke some preconceptions, but also raised new questions. It is clear that sharp changes in urbanisation occurred straight after the collapse of the Soviet Union (in most cases, this meant extensive privatisation and loss of public interest), but when the notion “post-socialism” is used it is often confusing whether it only refers to neoliberal reaction to state socialism and its implications or should socialist architecture and the way it is integrated into contemporary urban landscape be now also considered post-socialist. In other words, if public space planning difficulties, suburbanisation and a dream of an individual home, for instance, can be considered post-socialist reactions then would looking at Väike -Õismäe housing estate as a post-socialist environment just complicate and broaden the notion so that it loses some of its meaning? Would this imply that anything occurring in former socialist countries is automatically post-socialist? The notion seems to be useful in actually suggesting that there is no clear-cut distinction between socialist and neoliberal (and therefore also between East and West), but that we are looking at a rather reactionary transformation and adjustment process that is continuing also now, more than 20 years later. Looking at it from this perspective, the idea of being in “post-post socialism” becomes irrelevant – the way the conference was put together really seemed to propose a wider definition by bringing together speakers that analysed the socialist heritage (Lukasz Stanek) but also targeted the urban entropy of present day Tallinn (Francisco Martinez “On the urban entropy of Tallinn”, Tarmo Pikner “Entangled backyards of quasi-urban living”, Anna-Liisa Unt “Finders, keepers. A third landscape for a third generation city”). The central question when discussing post-socialist urbanisations seems to be how to plan privatised space and this was the focus of several speakers (Irina Paraschivoiu “From public to private. The case of Bucharest’s inner city development”, Nabil Menhem, Elena Batunova “Land property, from state control to full privatisation, where to draw the line”, to name a few). It is interesting to observe how there is more and more courage to challenge and question such processes like restitution and to talk about public interest when planning private space.

Questions in the air

The conference covered an impressive list of post-socialist (and still socialist) countries and the attention given to their specific post-socialist reactions gave an insight into the meaning of their common past. Perhaps a more general discussion of possible differences between post-socialist countries would increase an understanding of the complexity of the notion. It seems that despite the diverse content some link between the local academia and the city and the presented case studies was missing. While ULD has in previous years been a meeting point for architecture and urban studies and a possibility to discuss and find common ground, it seemed that there was less interest from local students, academics or practitioners this time, which leaves us asking how the event could have been more open, interactive and perhaps provocative. Fascinating case studies were presented but the complexities and the diversity of topics made it almost overwhelming at times and left little room for debating.

However, some general and very interesting questions emerged that also left us thinking how long does a country stay post-socialist and what developments does the term refer to? The questions raised underline the conferences aim and should perhaps even be considered the main output of the event. Naturally, these questions are contested and to a certain extent unanswerable. If we decide that there is no such thing as a reversal of post-socialist decision-making described as post-post-socialism but rather a continuation of adjustments, then maybe the discussion doesn’t need to stop at land ownership and planning. When we consider the common history of post-socialist countries, evoked by political history and reactions to it, as a context to understand the planning processes, then this in itself is a question of contemporary value. At the same time, a new interest in more future-minded developments about urbanisation is currently visible in Estonia. The Estonian contribution to the Venice Biennale this year deals with the notion of a highly digitalised country and the way in which these new digital connections must be taken into account when looking at urban planning.

It raises questions about the ways in which space is produced and changed by users connected to immediate physical space as well as digital space. Based on ULD examination of the complexities of post-socialist planning, a connection could be made to Estonia’s distinct future-mindedness. If planning becomes a problem due to privatised space and the issue of restitution, it can perhaps be interesting to look at projects that attempt solutions within these boundaries. Could digitalisation examined at the Venice pavilion, for example, offer a solution for a more democratic planning of private space?

The social dimension

Moreover, in social sense, post-socialist processes can include complex relationships between users of spaces we try to plan. Again, if planning in itself becomes problematic, small-scale projects might be at the forefront of possible mentality shifts, as attempted in Linnalabor’s Lasnapiknik within the soviet panel-housing district of Lasnamäe. How does this relate to potential attempts to bring change within the boundaries of the typically post-socialist planning issues in other countries? In short, after noting the boundaries that post-socialism presents us with, we can ask how these boundaries are currently dealt with at human scale. It seems that at least in Estonia, there is – among other things –, a strong will to move forward. This is not to say that ULD with its specific topic of post-socialist planning isn’t relevant anymore. On the contrary, finding commonalities between the different post-socialist countries gives us a deep insight into the complex and specific challenges that the notion sets for planners, architects and students involved in these practices. However, it would be interesting to see the ways in which the post-socialist discussion develops in parallel to other contemporary discussions about the future of urbanism. A sensitive exploration of post-socialist extremes between nostalgia and future-thinking could be the next step in the post-socialist discussion.

It seems that the key point to be taken away from emerging discussions on post-socialism, more specifically from those raised during ULD, is that urban space and any kind of landscapes can and should be looked at as ideological – be it socialist or neoliberal –, politics is reflected in the urban space we inhabit and create. Hopefully, encouraging critical thinking with such intensity continues.