TAB210

Lugemisaeg 6 minIs declaring the Republic of Estonia to be 95 years old something to be proud of or an unfair miscalculation? What moment can be considered the start of history? Is Hotel Olümpia an honest part of Estonia’s cultural heritage? Or a barn dwelling with a chimney?

This year’s Tallinn Architecture biennale (TAB) curatorial competition was won by a young architecture bureau, B210. Their successful idea, to discuss socialist space and architecture, did not impress me straight away. Again! Perky fancy dress parties and the TV series ENSV, countless research papers, special programmes and summer schools have long overused and analyzed the narrative.

But meeting with the curators was more convincing. The initiative that falls into the Cultural Ministry’s programme of cultural heritage is the only chance our generation has to fixate one state of transition. People aged 25-35 today live on the border of two histories – a decade there and the rest of it here. There is an experience of the Soviet Union, but it is not disturbing. This makes it possible to write it out in a more neutral manner. I felt that I have been personally touched, connecting a feeling of us. A mission emerged to unite, help and declare.

Memory

The history and heritage of Estonia is now and has always been stirred by someone else’s hand, sometimes even dictated and written down by someone else.1 The fact that Baltic-German heritage is not any better that Soviet heritage is more difficult to understand for my parents than for me – for me that time is not an absurd foolishness. Absurd foolishness was a queue for ice cream that lasted for hours or rather, the lack of such a queue. The kiosk was only open for ten days (in my life). There is nothing else repressive that I can remember from the late 80s. The rest of it was like it was. Tickets for public transportation were cheap, and coarse, wooden cultural centres smelled of slippers. When we took a trip to Saaremaa to visit my mother’s friend in the summer, the militia checked our faces and the trunk of the car. This crowned the travel fever of the summer.

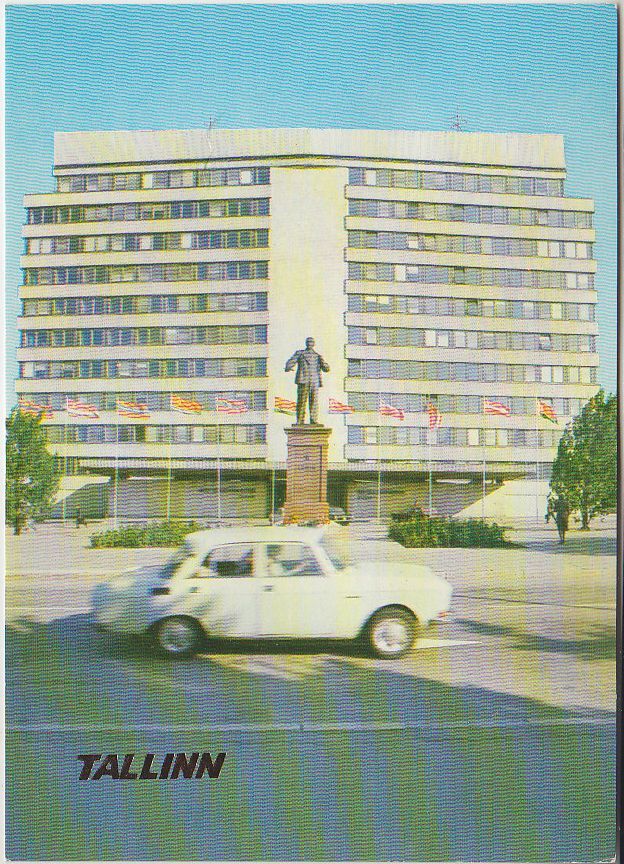

According to Halbwachsthe, collective memory is expressed through the support of the surrounding space.2 Therefore the urban space and architecture has a responsibility to shape attitudes and emotions. Changes are reflected in space very slowly, as houses and streets stand against history. If the first reforms after gaining independence were applied within months and economic and institutional changes maybe in a year, then the changes in urban space occurred much more slowly. The socialist heritage reminds those who experienced it of an irrational and unjust system. Decaying buildings, urban voids and places that have been filled with inconsiderate new functionality express the rush, after regaining independence, to abandon everything recent, delete or westernise.

For today’s decision makers (and the number of people who have no experience with the regime grows proportionally every day) the Soviet space is just a space, albeit maybe of poorer construction quality. Earlier heritage destruction tactics have been replaced with more considerate attitudes that arouse our enthusiasm to adapt new functions and needs into the old forms, rather than destroying them. 3

Curatoral exhibition

TAB, with three central and countless satellite events, culminates on the first week of September. In the international symposium the thematic framework (“Recycling Socialist Space” / “Taaskasutades nõukogude ruumipärandit”) of the biennale will be discussed by historians as well as space and form specialists. There is also an opportunity to get acquainted with the results of the vision competition that will be announced in March. The main event of the biennale is a curatorial exhibition that represents noteworthy objects from Soviet times in recycled form.

The intensity of space as well as use are factors that change in time – for example ‘modernist mini-utopias’ that were created to carry an ideology or hold large number of workers [4] can be, in the context of today’s economic interests, wiped clean of the former content (eg., H & M’s fast fashion in the Postimaja). Without changing the content, life would abandon the houses and they would collapse on their own (eg., Linnahall). The curators of the biennale invite us to see these changes not as vice, but as virtue. They offer misunderstood stars, which today function poorly and have undeservedly been forgotten or mistreated, for architecture bureaus to recycle.

Modernist space is an internationally known space, thus a guest arriving from almost any part of the world should develop some kind of a personal relation with objects from Tallinn. The depiction of history given by the institutionalised culture sphere [5] is not relevant here, as we wish to see subjective history instead of reflection in the recycled objects. Maybe that choice of field, opening and redefining the socialist architectural heritage and democratisation of Estonians’ collective memory, is somewhat like what Marek Tamm calls one of the central assignments of Estonia’s memory politics in his book. Rather than looking at things as black (red) and white (blue-black), meaningful discussion is created by this remix, which surpasses interdisciplinary, generational, and state-led opinions. The curatorial exhbition is a brief attempt to place things from the former times into a contemporary framework.

Worksheets

In the beginning of January, students interested in cooperation met. In accordance with the direction of the curators, portrait folders of chosen objects for presenting to the guests were developed. Old, current and future plans, photos, interviews with authors and users and fieldwork notes from heritage collectors were gathered. The general picture presented should give a similar starting platform for all the participants, according to which recycling could be started.

Architecture in Tallinn awaits regeneration. The Radiohouse, Flower Pavilion, numerous H-shaped school buildings, Kosmos cinema, the waiting pavilion of the Baltic Station and the foreign ministry are ready to be broken down, drawn over, defaced, or cleared up.

What would you do?

The organizer of TAB is Estonian Architecture Center.

The curators of TAB are Aet Ader, Kadri Klementi, Karin Tõugu, Kaidi Õis and Mari Hunt.

Biennale’s webpage.

1 Read for example: Marek Tamm “Monumentaalne ajalugu. Esseid Eesti ajalookultuurist”, Loomingu Raamatukogu 28‒30/2012.

2 Maurice Halbwachs “On Collective Memory”, 1980 [1950].

3 Taken from the notes of the lecture by Mart Kalm during the selective course in EKA “TAB 2013 RECYCLING SOCIALISM”.

[4] Curator’s comment for Eesti Päevaleht, 20.11.2012.

[5] Read texts by Marek Tamm.